When I were a lad I quite often worked, part time and for a pittance, on various farms round and about our village and it was then that I first fell in love with pigs. And it was reciprocated too, in a sort of way – largely contingent on me presenting myself regularly bearing armfuls of potato peelings and such like and leaning over the pigsty wall to do a little ear tickling. To this day pigs remain a love of my life and, given my scientific background, perhaps readers will be unsurprised when I find a convergence of the two too irresistible not to mention. Stay with me with some porcine science.

A friend (thank you, KS) has pointed me in the direction of a publication** in which the genome sequence of a female domestic pig, together with those of some of her relatives, has been described. Before we get on to why you less love-struck unfortunates should give a grunt about this, I must make it clear that no animals were harmed in unveiling this sequence. Rather, a small piece of an ear or a few teaspoons of blood were enough to grow cells from which DNA was distributed to the many research groups involved.

So what did the members of the Swine Genome Sequencing Consortium (what a lovely name) give us as the result of their labours? Well some things you would have guessed anyway: pigs have about as much DNA in their cells as we do (about 3,000 million base pairs). Of course they do: they’d have to be pretty similar for folk like me to go round falling in love with them. And within that sequence they have more genes (over 1300) encoding smell receptors than any other animal – which obviously helps if you have to root around in the woods for a bite to eat before becoming reliant on admirers bringing edible gifts. Of course, there must be a downside to being so olfactorily endowed but that's their problem. I wonder what they make of my macho aftershave?

|

| Meishan Pigs |

But what about the differences? Well, close though I feel to them, pigs and humans last had a common ancestor about 90 million years ago and a domesticated pig first trotted out of South East Asia about 4 million years ago. Separate strains of the domestic pig then evolved in Western Europe and East Asia and these diverged from the various strains of wild boar – though the separation is somewhat murky due to pigs being prone to roam, a habit that led to what is delicately called ‘genetic mixing.’ So beauties like our Lops turn out to be more closely related to European wild boars (Oh dear, better not offer any of our meat to UKIP supporters) than they are to Chinese pigs such as the Meishan.

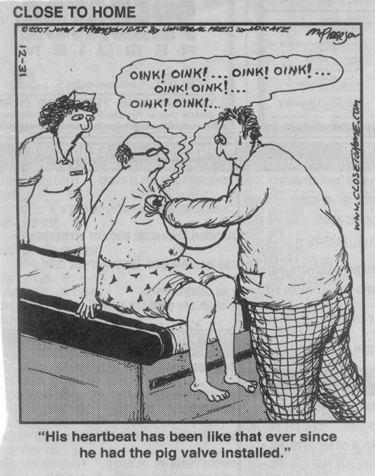

One of the things that happened as pigs went their separate evolutionary way is that their DNA became unusually prone to being broken. Although damaged DNA is usually repaired, two consequences tend to arise. Sometimes a gene just gets lost and this has happened with quite a few that we originally shared with pigs that enable us to taste things like salt: by losing that sensitivity pigs have acquired the ability to eat things we can’t. The other result is that pigs are quite good at shuffling bits of DNA to make novel genes (and hence proteins) – something called alternative splicing if you are interested. But perhaps the most important outcome is that pig DNA has acquired about 100 changes (mutations) that in humans are linked to increased risk of things like Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. Pigs have a long and noble history as good models for human disease and we use their heart valves in replacement surgery (how’s that for reciprocated love?). Having a peek at their DNA has revealed that they also offer a natural model to find out what happens in some of our worst afflictions.

Pigs: giving us their hearts, sorting out our frailties – and making more roast dinners than you can shake a trotter at. Everyone should love ‘em!

** Groenen, M.A.M. et al., (2012). Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature 491, 393-398.